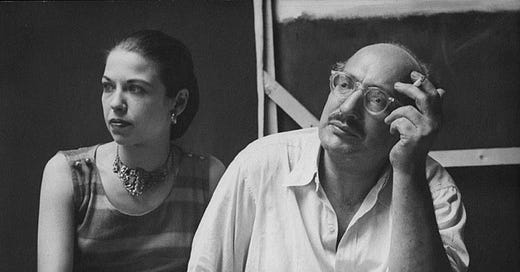

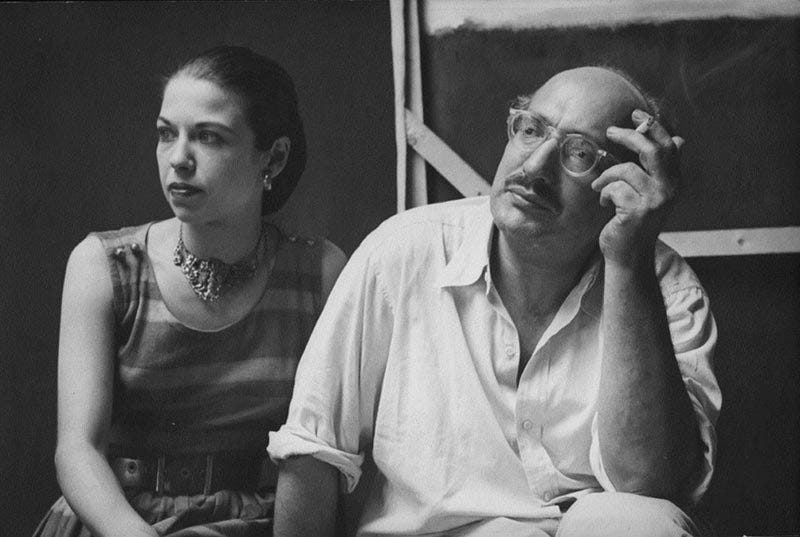

Mark Rothko: To Doubt Is To See

‘In a society where painters lack ‘official’ status, the power to confer legitimacy is held by museum directors and plutocrats.’

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A Secret Plot to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.