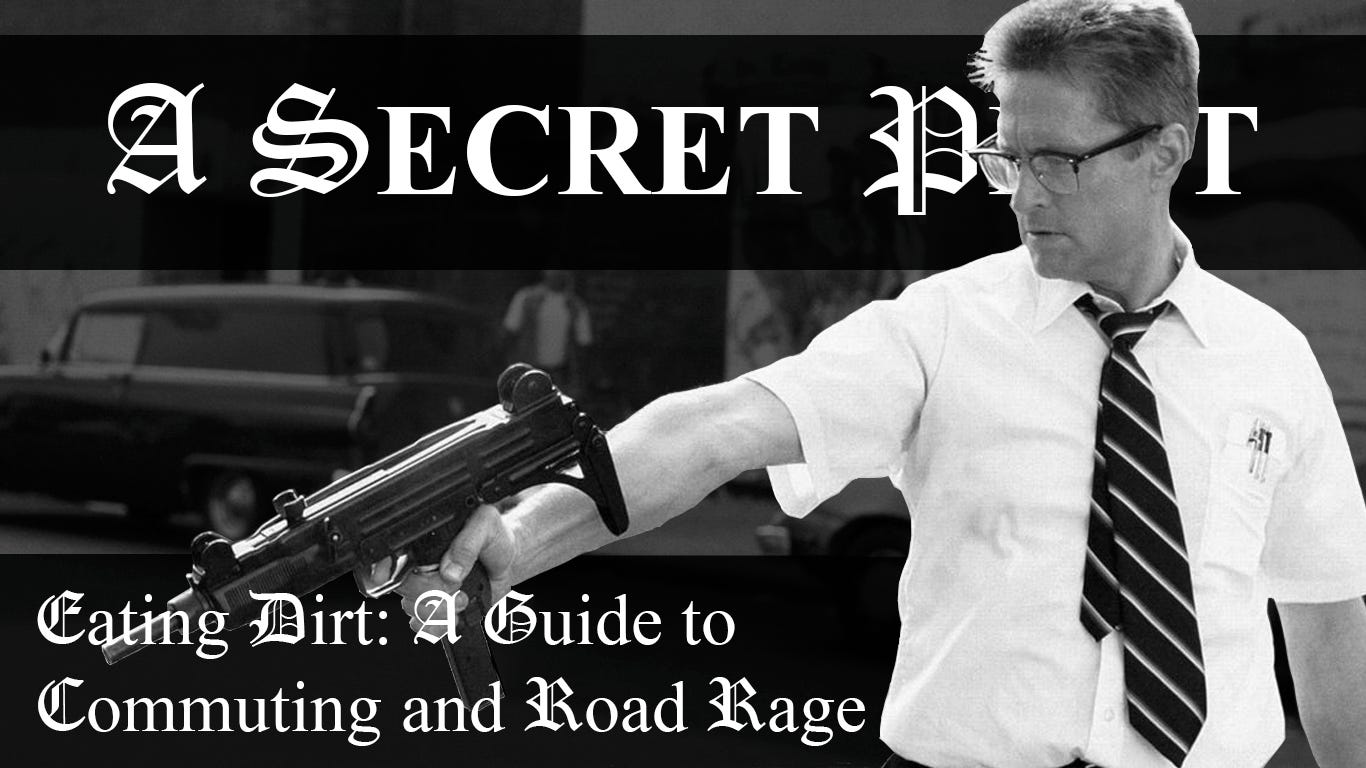

Eating Dirt

A Guide to Commuting and Road Rage

“Humans do not desire the good, the good is whatever they desire” – John Gray

To most people commuting is a nuisance and a necessary evil. It is a thing that almost every adult of working age does - every day. Commuting is one of the truly universal ‘political’ categories, because it is an activity shared by doctors and lawyers, baristas and roofers, and…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A Secret Plot to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.