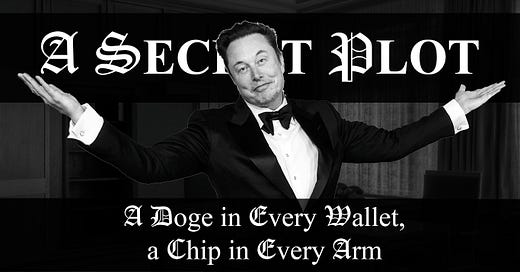

A Doge in Every Wallet, a Chip in Every Arm

The spectres of dystopia are once again being raised in popular consciousness, though the question remains, have they ever subsided?

With the recent successful Neuralink implant in the brain of an unnamed patient who was later able to play chess using only the mind, seemingly every Elon Musk fan and techno-optimist is onboard for a new paradigm. Yet, so jarring is the new development that even the mainstream is raising the question that many have forgot how to ask, where do autonomy …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A Secret Plot to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.